-

-

Video

-

Subject and master

The Honourable. Michael Kirby AC CMGSoon after I was appointed as a Justice of the High Court of Australia in Canberra, I participated in an interview for a television documentary in my judicial chambers in Sydney. The director was Frank Heimans, a greatly respected oral historian and filmmaker who already had dozens of admired film documentaries to his credit. He does his portraits, you see, on film.

‘I have a son, Ralph, who, I think, has gifts as an artist’, he said. ‘Oh yes?’ I replied, striving to look more interested than I really was. ‘Here, look at this portrait of an elderly relative. What do you think?’

I peered at the arresting image in the photograph held before me.

‘Good. Very good’, I declared.

‘Well, would you be prepared to sit for him? He has not yet produced a major work. He would like to start on you’.

I agreed to Frank Heimans’ request. Which goes to show how one never knows where chance decisions can lead.

‘There is only one problem’, I cautioned.

‘I just do not have the time to sit still staring into space for hours. Your son will have to come in the weekend when I am working at my desk. He can do sketches, photographs and notes, as he pleases. When he wants me to look up, he will have to say so and I will do it. However, so far as I am concerned, I will just have to get on with my work. Do you think he could create his portrait under such conditions? If so, we have a deal’.

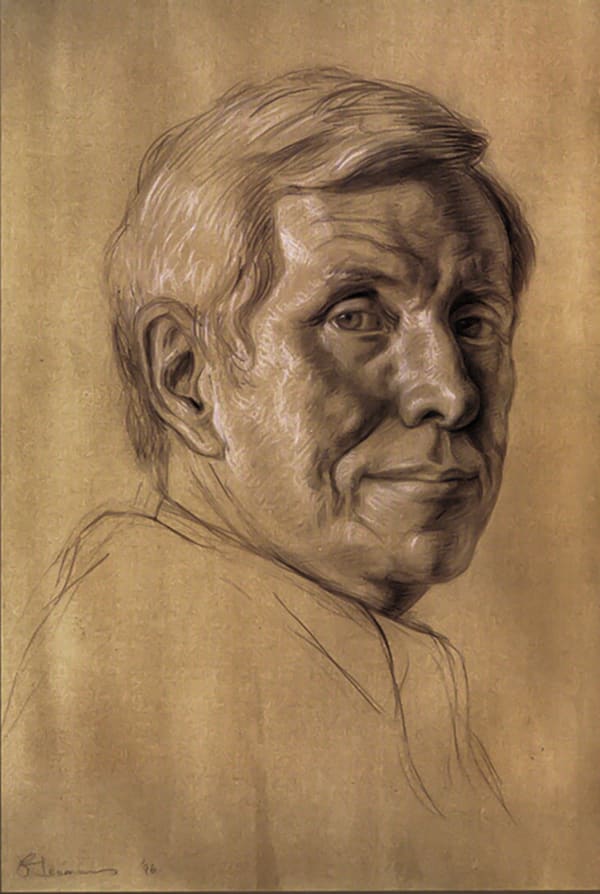

True to our deal, the young artist began appearing in my chambers over a couple of weekends. He was polite and respectful. But he had a glint in his eye. He knew where he was going. From time to time, he would call on me to “Look up!” And so I did. And ultimately, an extremely detailed sketch was produced, which, I later discovered, became the basis of my image brought to life in the portrait.

Because the canvas was so large, it came to dominate the Heimans’ home in Sydney. Ralph Heimans and his family lived with it for months. He has a passion about perspective. I put this down to his mathematical interests and training at university. The challenge is to portray the subject in relationship with the surroundings, animate and inanimate. It might be a London underground train. Or a university office. Or the Sydney Opera House.

In my case, the setting was one that would ordinarily never be seen: a private ante room to the judicial entrance to the Banco Court in the Sydney Law Courts Building. And there were all those judges arrayed in vivid robes. Most of them with their backs turned towards me.

By the time of this portrait there had been discussion in the public media about my occasional disagreements with judicial colleagues over this case or that legal principle. I had not yet earned a reputation as the ‘great dissenter’. That was to haunt my days in the High Court of Australia. In actuality, the turned backs in Banco might have had no significance other than that all of us were getting ready, ultimately in unison, to walk into a large courtroom that awaited our grand entrance. Yet for Ralph Heimans, the artist, those backs conveyed a different image. The image of isolation and loneliness that often accompanies a judicial life. But especially a judicial life that, more often than most, had displayed different values and sometimes differing outcomes for the problems submitted for resolution. Independence of the judiciary includes independence from one another. It is a precious feature of our legal tradition. If occasionally it means that backs are metaphorically turned against the judge, so be it.

A year later (for the portrait took many months to complete) I was accompanied to the Heimans home to view the finished product. My partner and my brothers, Donald and David (the latter by then himself a judge) each exclaimed on seeing the work. Magically, it seemed, Ralph Heimans had captured in his portrait a look I had given my brothers decades earlier. When, in our parental, home we were all studying late into the night, they would occasionally interrupt the older brother to seek information or guidance for their studies: ‘A pained look would come upon your face. It would show, at once, mild irritation at the interruption we were causing. But also a reluctant sense of the duty to respond. It is extraordinary that the artist has captured that conflict of emotions’. Whilst the viewer of the portrait might ascribe the inner judicial turmoil on my face to the turned backs of my colleagues, the artist and I shared a secret. It was that he had extracted that look by his command: ‘Look up!’

Radical Restraint, as the portrait was named, was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery of Australia. I still have, as a gift from the artist, the very detailed sketch used as the centrepiece of his portrait. The portrait and that sketch are on display in this Retrospective in Denmark. I am told that the portrait has proved to be one of the most successful and popular of the acquisitions of the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. It is full of rich metaphors. The National Portrait Gallery in Canberra immediately abuts the building in which the High Court of Australia performs its functions. As things worked out in that court, the metaphor on the large canvas of Radical Restraint became a kind of fulfilment for my many years of service in that Court. If I were superstitious, I would ascribe this to the occasional inclination of life to imitate art. And the danger of accepting the request of a noted filmmaker to allow his gifted son to use me as the model that helped to launch a magnificent artistic career.

Ralph Heimans has gone on to execute many important portraits of Royal subjects and other cultural figures, some of which are on display in this Retrospective. Also displayed are portraits of Vladimir Ashkenazy at the Sydney Opera House and a determined image of Dame Quentin Bryce AD, CVO, past Governor-General of Australia. There is even a second portrait in which I feature with the late Professor David Cooper AO of the Kirby Institute in Sydney. Inevitably, Radical Restraint is a favourite of mine. In these few words, I have attempted to explain how it came about. Between an artist and his model there are often secrets. It is a special experience to be the subject of such a master.