-

-

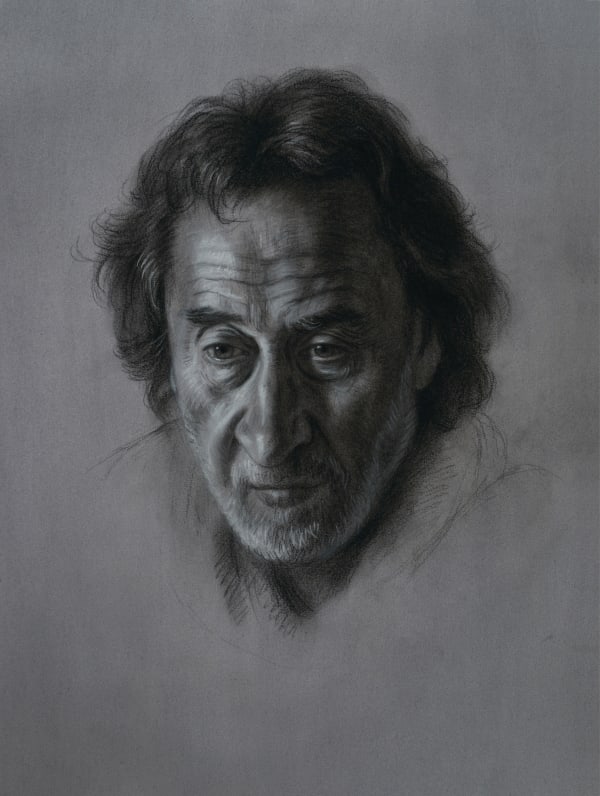

Howard Jacobson: "no sighs but of my breathing..." (The Merchant of Venice)2015

Oil on panel64 x 55 cm

Private Collection -

The Human Heart in the Human Face

Interview with Howard Jacobson by Jennifer ThatcherJ: Can you begin by telling me how you met Ralph Heimans?

H: We met five years ago at a big Royal Academy party for the Australia exhibition. It was a very starry one. His wife Tami came over and introduced herself.

J: As a fan of yours?

H: As someone who knew who I was, who had read my books. And there was something in common because they’re Jewish and so am I – although I try to hide it! And there’s also an Australian connection. I’ve written about Australia. I was with my wife and we thought they were lovely. I’d heard about Ralph’s painting of the Queen that had been defaced. We brought that painting up, and he said, would you like to see it? And they took us round to see it a few days later. And I liked very much what he did. And, right at that moment, an idea formed in my mind. I’d just been commissioned to write a novel in a series by Hogarth Press, who came up with an idea to have novelists do versions of Shakespeare. And I thought, it would be very good to have someone who could either illustrate them in some way or maybe do portraits of the writers. I thought that would be a good one. I didn’t say anything to him, but I talked to the publishers to see what they thought. Obviously, they’re always frightened about how much money is going to have to be spent for things like that, but I thought, well it’s a possible alternative to fancy photographs that sometimes get taken for the inside covers. So I talked to them and then I talked to Ralph and, before long, he was in conversation with them about it. And so he ended up doing portraits of most of the writers in that series. Some didn’t want to do it for reasons of their own. I was very keen. I fancied him doing my portrait. There was something about the way he looked at me. There was something about the warmth that we’d established between us as friends over the months that we’d got to know each other since that party. And I like his eye. I thought, I would like to be looked at by this person.

J: What was it about his eye? How would you describe his eye?

H: It was penetrating and genial. He is very, very sharp, very intelligent, very acute, but at no point does he give you the impression that he’s seen through you. He’s seen you, but not seen through you. And that struck me as a magnanimity. I thought it about the Queen and I think it about the portrait he’s just done of Prince Philip. He’s not an ironist. Although there’s something deeply ironical about what he’s doing, when you think about it, doing modern characters in that form. It’s not ironical in the belittling sense, it’s ironical in the sense of bringing disparate forms together and making you look at things in a way you’re not accustomed to. And so, it got fixed up that he would do some of the writers in the series.

J: Were you the first?

H: I probably was the first. Because it seemed to both of us that if he was going to persuade the publishers that this was a good idea, he wanted an example. And since we’d started off the conversation and I was the second novelist in the series anyway (Jeanette Winterson was the first; for some reason she didn’t want the portrait doing) ... And he came round to take photographs to begin with. I was very busy writing the book then. I didn’t have a lot of time to give him. And he said, no, I don’t need that. I’d rather just come around and we’ll talk, and I’ll take photographs.

J: How far had you got in writing Shylock Is My Name when he took those photographs?

H: Maybe I was a third of the way through. I was certainly absorbed in the whole question of Shylock by reading around Shylock and by reading everything to do with Shakespeare, Venice and matters Jewish. So maybe I was looking more Shylocky than I would normally have expected to look. Maybe that’s what he saw. But he came around; I remember him quite vividly. We chatted about all sorts of things. And he said: Don’t pose, just let me take photographs.

J: Were you wearing that scarf anyway? Or did Ralph bring it for you to wear?

H: I don’t think I would have been wearing that scarf indoors. In fact, let me look at the painting. It’s not in my eye-line now but it will be in a second. I wear scarves a lot; he’d have seen me wearing scarves.

J: So it felt natural to wear a scarf, but he may have added this particular one as a kind of Shakespearean prop?

H: Yes, that’s right. It’s a white, silky-looking scarf. I don’t have such a thing, so he’d clearly invented that. Well, it’s of the period and it’s a very nice feature in the picture because it takes light; it receives light and it throws light back into my face. It’s a clever choice.

J: Did he direct you in any way?

H: Not at all. He was very determined that I just talk. And, in fact, I think the photograph that got him most was a photograph that he took at the moment when I was making a decision, and that decision was whether or not to have a biscuit that my wife had brought up. She’d brought up a plate of biscuits for us to have and, as always when someone comes to visit, the visitor never has the biscuits and I eat all the biscuits. And we’d been talking about that and I’d been thinking, I must stop doing this. Do I have a biscuit or do I not have a biscuit? And in that moment of deciding about the biscuit, it seems that he or his camera had seen all that they wanted to see: the seriousness of the man perplexed. And that’s the expression that he got. And when I saw the painting, I loved it and I actually bought it. It’s an act of vanity, I know, but I wanted it.

J: Has your feeling towards the painting changed since you’ve owned it? Is it displayed prominently?

H: It is displayed prominently – well, reasonably prominently. You don’t want to stick people with it the minute they come into your house! And maybe it’s an immodest thing to do. But I feel what I’m showing is not me but Ralph. I’m pleased to have a painting by Ralph on the wall. It took my breath away when I first saw it. It doesn’t take my breath away now because I am accustomed, but the first shock of it – well, it’s rather tragic, even though I know it’s only a biscuit. But behind one decision is, of course, every other decision. What he’s seen, too, is some of the melancholy of Shylock. We talked about Shylock a lot. We’re both interested in the whole argument about is this an anti-Semitic play, which, to my mind, it is absolutely not. And I talked to him about how I’m touched by Shylock in the play, particularly his remembering his wife. Now, it could be, that it’s nothing to do with the biscuit and it’s the moment when I’m talking about Shylock remembering his dead wife, who is mentioned in the play only once when he hears that Jessica has run off and stolen the ring that his dead wife Leah left – it’s my ring, she gave it me when I was a bachelor, he says, I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys. I was very interested in that moment of the play. In fact, I wanted to call my novel A Wilderness of Monkeys because that’s the moment in which the play absolutely piercingly – briefly but piercingly – opens up Shylock’s heart, and that’s the moment that makes it impossible for one to think about it as an anti-Semitic play because that’s Shakespeare the great dramatist showing you, this is what it is to know another person. The Venetian ratbags think of him just as ‘the Jew, the Jew’, but at that moment, you don’t think of him as ‘the Jew’, you think of him as the father and the lover, the young man, the older man. And it might have been while I was talking about all that and feeling my way towards Shylock’s melancholy and perhaps identifying a melancholy streak of my own that Ralph saw what he wanted to see.

J: There are multiple layers within the portrait, then: the writer grappling with the responsibility of rewriting Shakespeare, and a particularly difficult, controversial play at that; but also you channelling Shakespeare or perhaps the character of Shylock as some kind of conduit?

H: That’s an interesting way of putting it. A conduit back into myself, you mean? I don’t know whether I thought that. But I felt a connection. I felt that I knew how to read this play and that the best critics of the play that I’d read knew how to read the play and didn’t talk about it as just some ugly, anti-Semitic play – only that aspect. I was interested in Shylock’s sadness and hated the way he’s jeered at in the play. I don’t mean I hated Shakespeare for doing that; I think what he rendered was the particularly vile cruelty towards him and it’s one of the saddest things in Shakespeare. And we’d been talking about all that. And maybe that’s there in the picture. I remember joking to him when I saw it that this was the nearest I was ever going to get to being looked at by Rembrandt. And it is very Rembrandty. And of all portrait painters, Rembrandt is the one I most admired since I was a teenage boy. As a student, I had Rembrandt’s self-portrait reproduction on the wall. Nobody sees the human heart in the human face the way Rembrandt does. Nobody sees the inner man or woman in the eyes the way Rembrandt does. Just the weight, the sort of animal weight, of being a person is what Rembrandt gets. I feel that there’s a touch of that in this.

J: Did you think about visual representations of The Merchant of Venice, or other Shakespeare plays, when you were doing the research for your book? I was thinking of portraits by Johan Zoffany or Maurycy Gottlieb, for example.

H: In my version of the play there is a painting, which I thought would be appropriate. Because in my novel, my Shylock is divided in two. There is an actual Shylock himself. That was the second version of my novel because at the beginning I thought I’d find a modern equivalent. Then I thought the modern equivalent doesn’t do the job as well as Shylock himself, so I kept them both. And my modern equivalent is an art dealer of some kind. He’s involved in an argument with other art dealers in the north of England, who are the equivalent to the Antonios and so on of the play. There is an issue around a painting. In fact, the American edition in front of me at the moment shows that painting, Solomon J. Solomon’s Love’s First Lesson. I thought it would be interesting if my modern collector would be interested in Victorian Jewish painters, so there are speculations about Jewish painters and particularly Jewish painters from the north of England in the novel. I’m not sure if any of that is justified by the play …

J: In your version, you also give Beatrice a line about Rembrandt’s portraiture.

H: You’re quite right, so I do. And she talks about the darkness and the light. I suppose I was thinking about that: the power of light in art, the force of shadow and obscurity in art, and that’s something you certainly see in The Merchant of Venice itself, where the play does vanish into shadow; it’s shadowy, and then sometimes glaringly, unbearably bright.

J: What did you think about the title Ralph gave your portrait, … no sighs but of my breathing …, which sort of casts you into the role of Shylock?

H: That entirely came from him. And if he was thinking of me as Shylock, given how I was talking about Shylock, that wasn’t a problem. I mean, once upon a time, if someone had called me Shylock I would have taken it as the deepest insult. But given how I was thinking about Shylock, given how we were talking about him together, no, I rather liked that. And it’s funny because the first two people who saw it – my assistant and a neighbour – they both actually guessed, and my assistant shed a tear. He looked away; he said, I find this deeply, deeply upsetting. I think that he felt that the painting carried a depth of feeling, and I think Ralph’s work does because he is a person of great feeling himself – because of what he is doing, because he is evoking older styles of painting, and not in the spirit of pastiche at all. I felt we were doing something similar: I’m aping but at the same time writing a sort of critical essay as well as a novel about Shylock and so I’m going back in time, thinking about now and then; and Ralph’s done the same in his paintings. And you get a great depth when you go back that way, because you’re piggybacking on older feelings and there’s something about thinking deeply over time. We live in an age which is mad on now, where people have no memories. We think that everything is of the present, and we must catch the fleeting moment on a screen. What Ralph has done and what I’ve done, in our separate ways, are acts of remembering. And they are acts of remembering full of feeling.

J: How do you feel your portrait compares to the other five Shakespearean portraits?

H: Ralph’s done terrific things. The Margaret Atwood is very, very good indeed. I like them all. I think it lent an added gravitas to the series. I’m the saddest of them.

J: Your portrait is the only one that doesn’t have an elaborate background, whether architectural or landscape. It’s the only one floating in darkness.

H: It’s my soul. He’s painted my soul.